Why Generalists Make Better Product Managers

Research suggests that generalists are more creative, better problem solvers and lateral thinkers — aka ideal Product Managers

Speaking at Leading the Product Sydney 2019, on Evolution of Product Management and slides hereLast year I spoke at Leading the Product Sydney on the Evolution of Product Management where I talked about how Product Management has evolved over the past couple of decades, particularly how the role has been reshaped in a number of distinct ways.

One of those ways I discussed was how the role has shifted towards being a “jack of all trades” — a generalist role over a specialist one.

Let’s be honest, there’s not much depth you can go into in a 20-odd minute talk so I wanted to continue the conversation here and dive deeper into this topic — why generalists make better Product Managers.

Happy 89th Birthday Product Management!We often think of Product Management as this new thing. Many companies have ‘shining thing’ syndrome and are jumping on the Product Management bandwagon. But the truth is that Product Management is not new — in fact, Product Management has been around since 1931.

However one of the biggest changes that has happened since then is that our world has become increasingly more complex and volatile — we are not the same place we were 20 years ago let alone back in 1931!

The rate of change has increased and disruption is the new norm. As a result, the number of competencies, knowledge, and shear ground you need to cover as a Product Manager is immense.

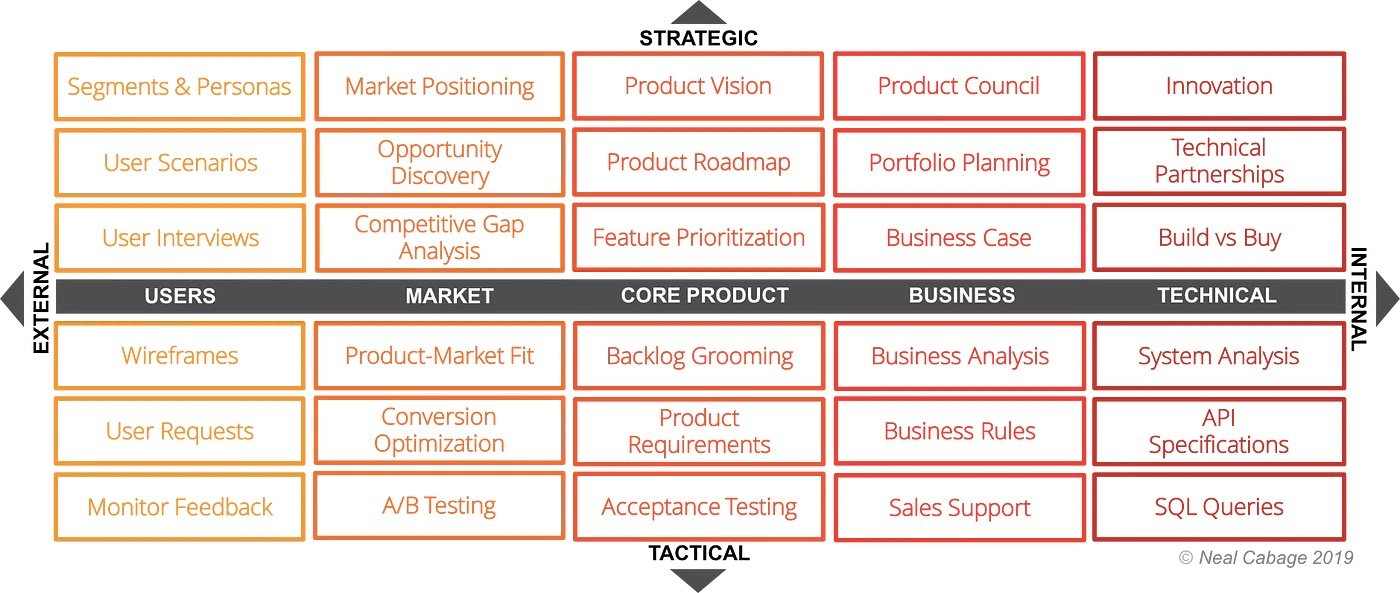

I love Neal’s product matrix! It gives you an idea of just how many facets there are to product (Credit: Neal Cabage)The truth is, no single person can be across all of these — not at least doing them effectively.

As a result Product Managers need to lean on the expertise of others, namely a product team. In many ways, product management today has become a team sport — a real group effort.

Product is a team sport.

Consequently, the role starts to move away from being a specialist role and towards a generalist one — you become broad in your skillset from understanding UX, discovery, stakeholder management, tech, process, strategy, etc.

This is crucial for Product Managers today. You need to understand how the many facets of product management interplay so that you can know how to best leverage them to build successful products — do I leverage marketing or the growth team for this? — without this breadth, you may miss a crucial piece of the puzzle.

This doesn’t mean that you don’t become an expert in your own right and depending on the organization and product you work on you may go very deep in one or two things. But the reality is that it is impossible to go deep across all the different aspects of product — you need to achieve success through others.

As such the best Product Managers today are not these all-singing-and-dancing one-person-bands, rather they are like conductors at an orchestra — they may not know how to play every instrument but they know enough to get the most out of each individual and keep everyone in step.

Now you’re probably thinking, what about the old adage of “jack of all trades, master of none”??

Well turns out that being a generalist and having broad set of skills is in fact ideal for a role like Product Management — it’s actually a strength in the right application.

Why generalists make better Product Managers

In the book ‘Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World’ by David Epstein, he explores a vast amount of research and science behind where generalists triumph over specialists.

Profoundly, the relationship he discusses at the end between having a generalist who has access to individual specialists sounded akin to the construct of a product team — a generalist Product Manager with individual specialists in a Product Team (more on this later).

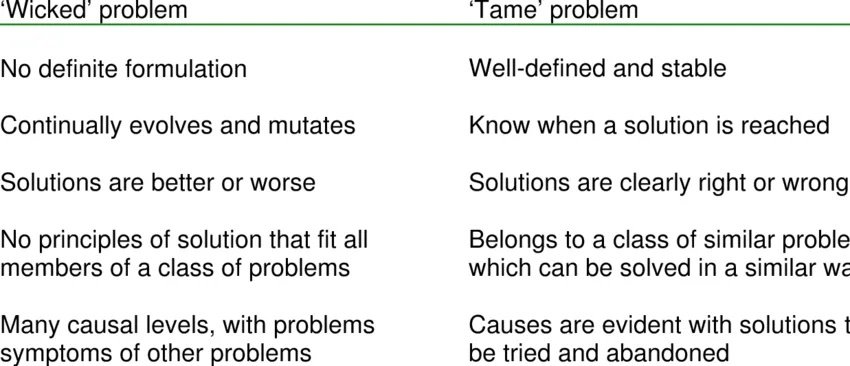

But one of the main reasons why generalists triumph over specialists is when it comes to dealing with wicked problems.

Rapid digitalization and an ever increasingly complex world has us facing more wicked problems than we had in the past.

It has required us to shift our approach to be more adaptive and use approaches like rapid experimentation from The Lean Startup — a new problem = a new approach.

New approaches aren’t just in structure and process alone. Epstein walks through a vast amount of research in his book that suggests people who have a broad “range” of skills — generalists — especially in adjacent fields to their core domain, make better abstract thinkers.

They are better at drawing parallels between other domains to solve the problems of their core domain — this is the essence of lateral thinking.

Lateral Thinking: noun

“The solving of problems by an indirect and creative approach, typically through viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.”

Epstein also explores the other side of the coin. Those who have become deep specialists in their domain.

Although being formidable at their craft their depth of expertise can often result in a phenomenon referred to as cognitive entrenchment.

Cognitive entrenchment is a fancy psychologist term for “when all you have is a hammer everything looks like a nail”. It's the phenomena where as you acquire deeper expertise in a single domain you actually become less able to think laterally and apply abstract thinking. Your hammer makes everything look like a nail, thus narrowing your world view when it comes to problem solving.

“as one acquires more domain expertise, one loses flexibility with regard to problem solving, adaptation, and creative idea generation” [on cognitive entrechment]

Cognitive entrenchment is precarious when you consider the craft of Product Management. When the entire job is to solve problems, adapt, and generate creative ideas! It’s as if the role was designed for generalists.

‘Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World’ by David EpsteinEpstein however, is quick to point out that being specialist vs generalist is neither better nor worse, it’s contextual — certain situations will require deep expertise whilst others demand more abstract thinking.

Product Management is one of those roles which is geared towards generalists given the need for problem solving and wrangling wicked problems. Engineering however is a role that is definitely more suited to deep expertise over a broad range of skills.

However as you can probably tell you need to have both.

Often those with range — generalists — are missing crucial pieces of the puzzle when it comes to problem solving. Their lack of deep expertise leaves them short, however what they gain in abstract thinking and the ability to connect two seemingly unrelated ideas together is their superpower.

By having a mix of both we can bridge the gap between them.

A structure that works well that Epstein shares in his book, is when a generalist has access to the deep expertise they require — access to specialists whom they can ask questions and elicit the necessary information they need to problem-solve.

In many ways, this is exactly how product teams operate. A mix of generalist and specialist roles. Where generalist roles, like Product Management, use their abstract thinking superpower to ask the right questions and leverage the deep expertise within the team to solve customer problems and drive outcomes.

Expanding your range

A perhaps controversial topic is the frequent question of “how does one get into Product?”

Up until recently, there has not really been a single way to get into Product Management — there were no Product Management specific degree, nor were there any entry-level Product Management roles.

More recently organizations, particularly the likes of Google, Atlassian, etc saw this gap and have started to fill it with the creation of the Associate Product Manager role. A junior Product Manager role that is often filled by exceptional university graduates.

However, I’ve often found people are divided in two when it comes to this notion of a graduate-entry level Product Manager role.

On one angle there’s the benefits of clear entry to product, clarity of career progression, and a pathway to coaching the next lot of future product leaders.

But there’s another camp of people who would argue that Product Management is not a role that can be taught in the classroom — it requires battle scars of execution and being in the trenches. Some surmise that it is therefore a role that requires people to do a tour-of-duty in another role within a product team first — to cut their teeth on Engineering, Design, analytics, etc.

However, neither deny the importance of a role like the Associate Product Manager play in grooming the next lot of Product Leaders. But one side of the fence will argue against the notion that it can be filled by recent university graduates. That to be an effective Product Manager one needs to have had a bit of experience in a product team first.

I can see benefits and arguments for both and am honestly undecided in where I sit.

But the notion that generalist skills increase your abstract thinking ability is an interesting layer to put on top of both those arguments.

You could perhaps deduce that this supports the latter argument for a wavy path into Product — it scientifically will make you a better Product Manager!

But with all that said, there are many other ways to “expand your range”, as David Epstein puts it, outside of actually doing another role.

Photo by Thought Catalog on UnsplashEven before reading ‘Range’ I had been advocating for Product Managers who I coach to branch out. Don’t just go and do another Product Management course — half the time you spend $2k and realize that you knew most of it already — rather go learn something different.

Go do a coding course (one person I coach did! They’re now certified in AWS). Or if that’s too much of a stretch jump on a UX course.

I’m even a fan of going more outside the box — why not take an art class or something?

Another Product Manager I mentor took several painting lessons. They now know a whole lot more about colors, perspectives and depth which they now draw upon when it comes to branding and UI design — abstract thinking at work right there!

The cost of courses aside, there are other great (and free) ways to expand your range. Volunteer your time or even take up a hobby.

My hobby is guitars and fitness, the skills I’ve learned from deliberate practice, improvisation and creativity from playing instruments transfer more to Product Management than you’d imagine.

It may seem counter-intuitive but the research is there to back it up.

It’s not always becoming more specific within the craft of Product Management that will make you a better Product Manager — although identifying gaps and closing them is crucial — but going too deep, too specialized, runs the risk of falling into the cognitive entrenchment trap and ironically making you a worse Product Manager than when you started.

Paradoxical I know! But it may just well be doing something completely “left-field” that will make you a more creative, a better problem solver and therefore a more effective Product Manager.

After all, it’s hard to argue with science!

📣 FYI: If you got value form this, I offer self-paced deep dive courses into specific PM topics like Prioritization, Stkaeholder Management and more over at productpathways.com.

Checkout Product Pathways YouTube channel here, for videos on all things Product, Leadership and Business.

Learn product online at ProductPathways.com and free on YouTube @ProductPathways.