Is Your Agile Transformation Failing, Too?

A dive into behaviour change to understand why

Photo by burak kostak from Pexels“Change is hard because people overestimate the value of what they have and underestimate the value of what they may gain by giving that up.” — James Belasco & Ralph Stayer

Change is hard. We all know this. Organisational change starts with personal change. Again we all know this. But if we know these things why do a staggering amount of transformations still fail?

IBM a few years back stated that 84% of Digital Transformations fail — although there is a lot of “grey” area around what constitutes as “failure” still 84% is a staggering number! What interests me the most is why this is the case? As a fellow coach Tanner Wortham brilliantly provoked “If this agile thing is so great, then why doesn’t it always stick?”

Great question! After all, we all know we need to be more agile, more adaptable and responsive to survive — no one is arguing about the validity of agility anymore — however there is still a gap between what we know and how we behave.

Unfortunately this is largely due to the fact that behavioural change is not so straight forward. Much like how we know we should eat healthy, exercise, spend more time with friends and family, not looking at our phones 80 times a day, but simply knowing these things doesn’t mean we do them — and agile is no different.

Knowing ≠ Doing — a very real theory

So, why is it so hard to turn what we know into what we do?

Photo of Dom Price’s keynote at X4 Sydney 2019

Behavioural Change and The Fogg Behavior Model

Let’s consider a company and those within it have been performing a particular habit for many years, say the habit was Taylorism, or using deadlines and the stick method to get things done. These habits are then often reaffirmed by either a) a promotion, or b) a fat bonus at the end of the year, or even c) simply keeping your job. Over the years the people within this company continue to strengthen these habits and climb the corporate ladder (a perception of success) by doing so. These habits are reinforced further over many years and have now not only become hard to modify but also believed to be impossible to completely get rid off — and therein lies the problem.

“This habit was never really forgotten, […] It’s lurking there somewhere, and we’ve unmasked it by turning off the new one that had been overwritten.” — Kyle Smith (McGovern Institute research scientist)

So how do you change a habit or behaviour?

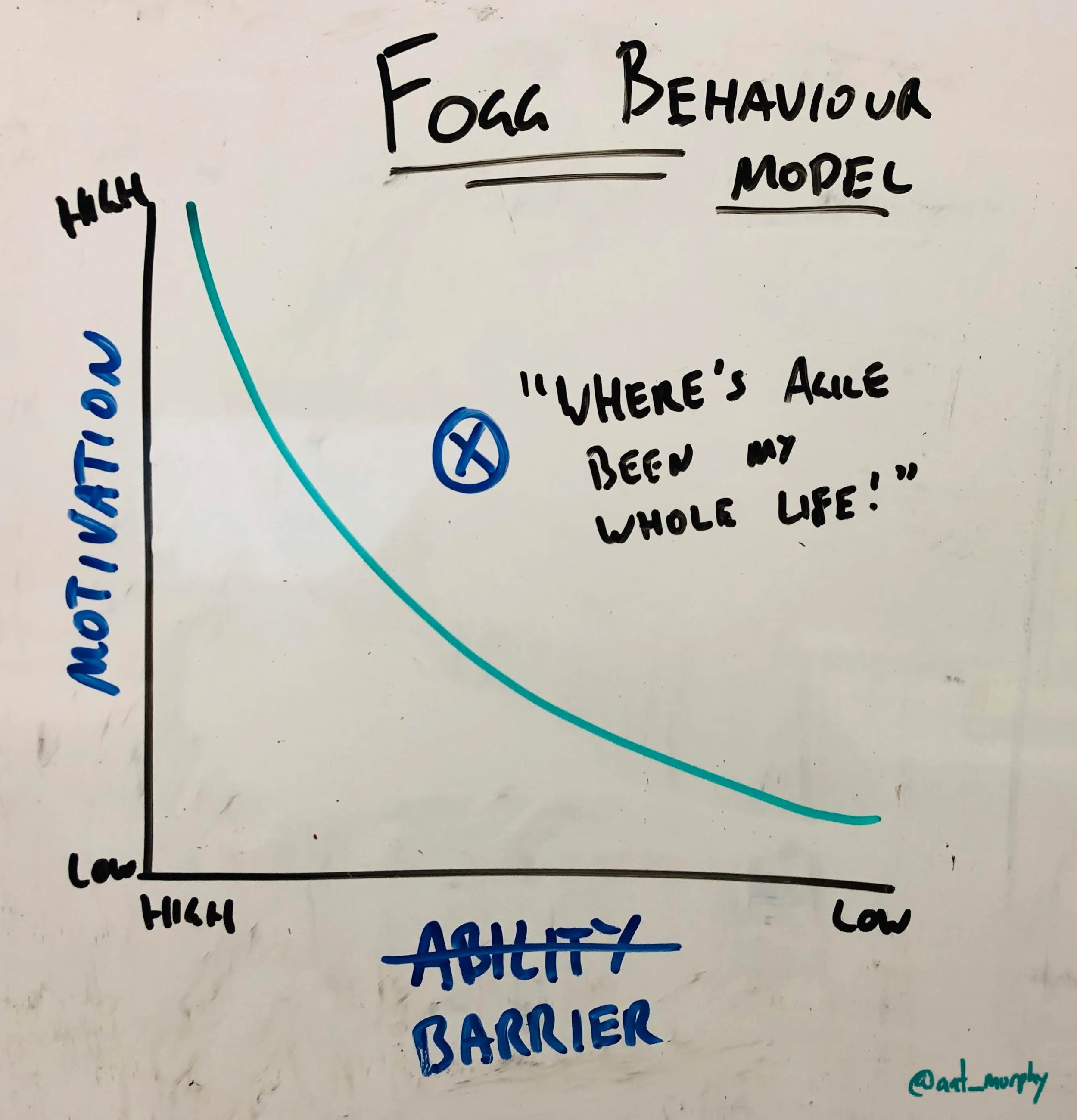

Fogg Behavior model with my adaptation of reframing “Ability” to “Barrier”The Fogg Behavior model details that in order for a new behaviour (and ultimately a habit) to be taken up there needs to be enough perceived utility (motivation) in the new behaviour and the barrier (the person’s ability) to perform the new behaviour needs to be low enough relative to their motivation — in other words if something is very difficult to do, then one needs to have a higher level of motivation to do it, as opposed to something which is easy would require a lower level of motivation.

For example, think about getting up at 4 am to go to the gym, the barrier is quite high so either you’re motivated enough to do so or you’ll hit that snooze button and tell yourself that tomorrow will be different. Now, compare that to giving up caffeine — you’re at work and 10 am rolls around, your morning coffee habit kicks into gear but deciding to order a decaf instead or perhaps abstaining altogether is a much lower barrier than that 4 am wake up call.

So where does agile sit on the Fogg Behavior Model?

In my experience agile will sit at different spots based on an individual's perceived value and motivation, as well as how hard it is for that particular person to adopt this new way of thinking.

Take the earlier example, those who have spent years, perhaps decades, building habits of working in a “non-agile” way — for them the barrier to change would likely be quite high which dictates that only an extremely high level of motivation would result in a successful change in behaviour.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” — Upton Sinclair

Conversely, if we took a recent university graduate — besides being fortunate to have a higher level of neuroplasticity — they are likely to have had little-to-no experience working in any other way, their barrier would arguably be much lower than those who have been institutionalised by decades of Taylorism.

💡Ask yourself, what’s your reason for undergoing this transformation? Is it high enough to overcome the change barrier?

Unfortunately, in my experience the decision to “go agile” and change is often not their own — rather they are part of a big machine, an employee along for the ride as someone towards the top of the ivory tower decided that “going agile” was a good idea.

I had one exchange that will always remind me of this lesson — I was coaching a relatively new-to-agile-team and was helping to facilitate their first retrospective. I cannot remember the specific question which triggered it but I will never forget the response I got! A team member sitting at the back of the room with her arms crossed bluntly said “Sorry, but right now you are challenging my job satisfaction. I like to write code and develop applications, not sit in meetings!” — to say I was surprised to hear that is an understatement but I immediately thanked her for the candor and courage to speak her mind. That moment stays with me as a stark reminder that often when places undergo such transformations, it’s less of a “wooo, can’t wait to go agile!” and more of a “wait you want me to do what now!?”.

Where transformations get stuck — ‘Doing’ vs ‘being’ agile

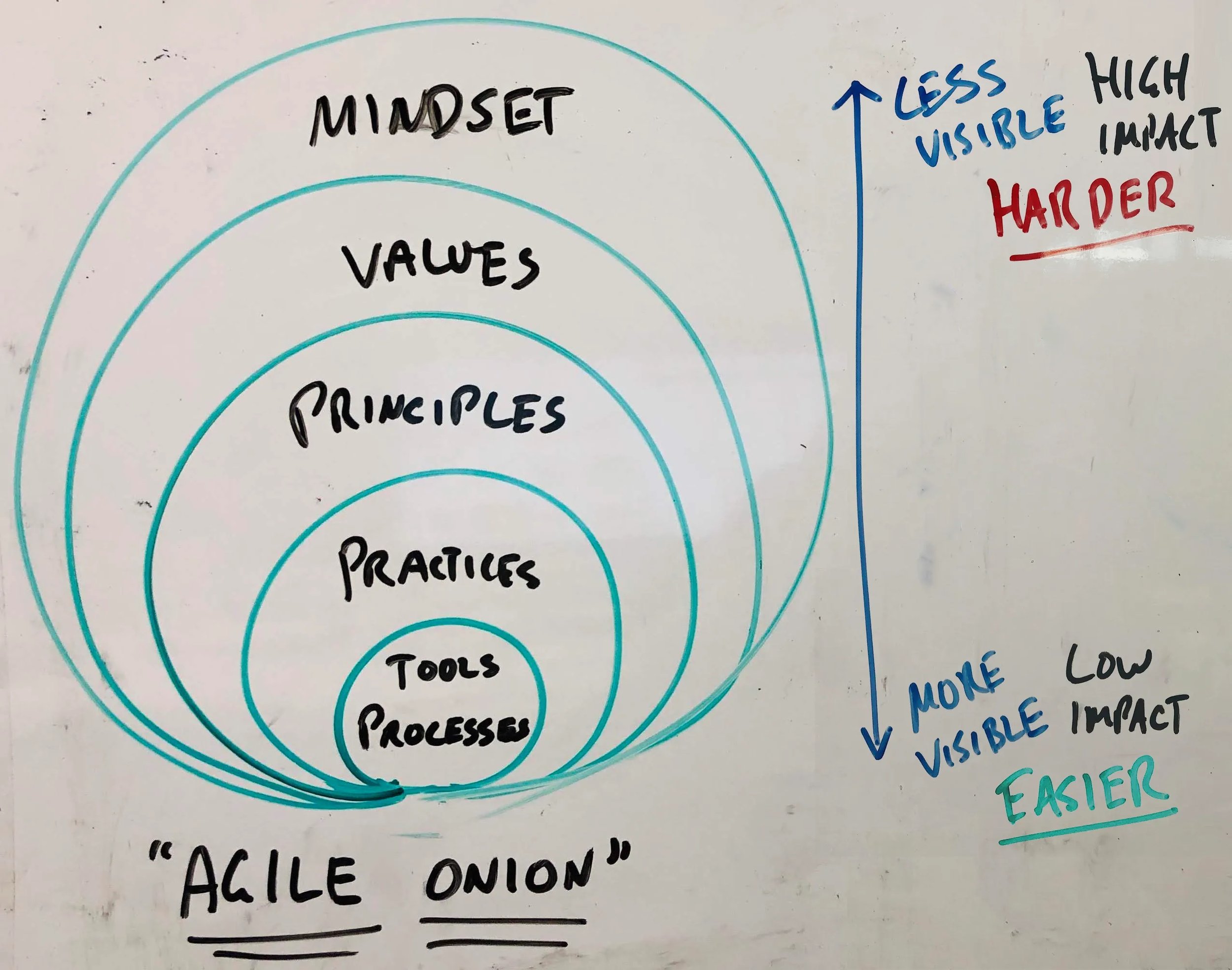

Dark Scrum, Fake-agile, whatever you call it, we’ve all seen it — organisations adopting agile in name only, reduced to only following a set of processes and tools and failing to transcend and apply the values and mindset — ironically too, as the first value of the agile manifesto states “individuals and interactions over processes and tools”.

Many of you will be familiar with the idea of ‘doing’ vs ‘being agile’. Today the number of these companies ‘doing agile’ greatly outnumber those who are living the agile mindset. Many of us change agents are often found in the midst of the ‘doing agile’ tide, furiously paddling against it but with little-to-no avail — why is that?

The “agile onion”This got me thinking about the “agile onion” as it has been commonly dubbed. The “onion” visualises many layers of agile, from tools and processes at the bottom, being things which have high visibility but a low impact. And at the top is values and mindset, which although are less visible have the greatest impact.

If I were to split the onion in two, one could easily delineate between:

“Doing agile” — i.e. following certain practices, tools and techniques, and;

“Being agile” — i.e. living the mindset, values and principles.

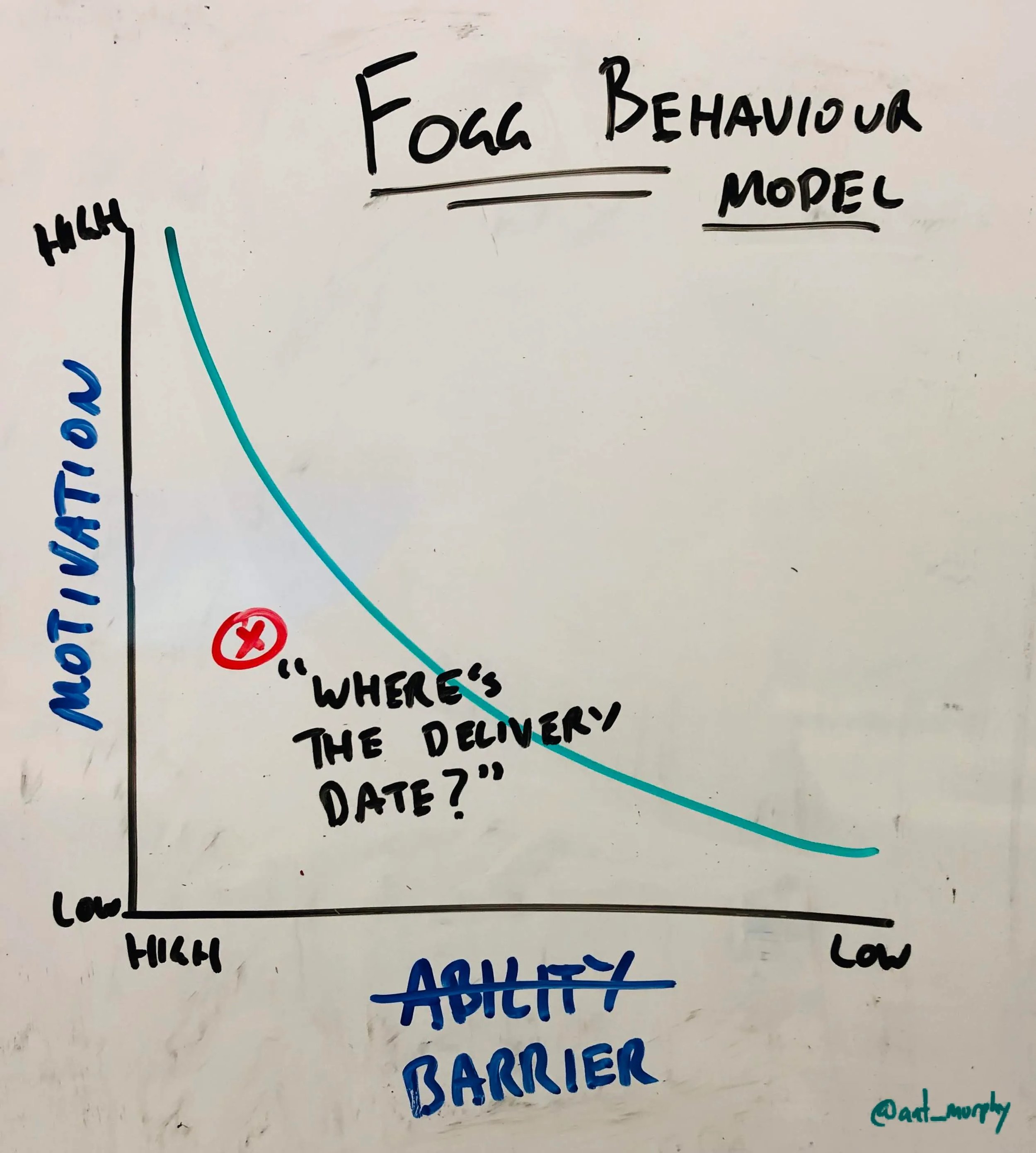

How would ‘doing agile’ compare to ‘being agile’ on the Fogg Behavior Model?

A generalised mapping of the ‘agile onion’ onto the Fogg Behavior ModelThis by no means is how it would look for everyone — I wouldn’t be writing this if I hadn’t managed to make the transition myself — for me and many others, the intersect of the whole “agile onion” falls within the successful change side of the curve. But for many organisations their agile journey looks much like this, with ‘doing agile’ on the successful adoption side and the ‘being agile’ on the non-successful side.

But what about those, like us, who do change?

Yes, statistically there will be some who will make the switch to ‘being agile’ — either they have a greater personal motivation for change or their barrier to change is lower than the rest. Whatever the reason there will be some who make it — but the burning question is, are the few who change enough to change the rest of the organisation? Can the few change the many?

That I’m not sure about, potentially in certain situations yes, but my experience has not shown this to be true. Rather the law of critical mass tends to make its mark — if you are not familiar with the law of critical mass, it is a social dynamic which states that only when a large enough portion of people have adopted the change will it become self-perpetuating and much like a snowball rolling downhill will also attract change in others.

An interesting concept and one which warrants further exploration but at least at face value, it suggests that organisations who have had years of reinforcing anti-agile behaviours are perhaps doomed to never transcend beyond agile practices — simply because the majority of the organisation have been pushed into the unsuccessful side of the Fogg Behavior Model — which starts to draw the conclusion that perhaps only younger organisations or those whose culture are already agile-friendly will be able to achieve an agile mindset.

“Changing behaviour works only if it can be based on the existing ‘culture’” — Peter Drucker

If so, what hope does that leave for older organisations where they have been institutionalised by decades of anti-agile patterns? Will they ever be able to realise the agile mindset or forever reduced to only ‘doing agile’?

Surely, there’s something we can do about it?

Michael Sahota is often known to suggest working the culture angle — as he states in his book — “An Agile Adoption and Transformation Survival Guide: Working with Organizational Culture” — we should be starting with culture and work with it rather than oppose it, which as he states is often what agile does — create friction against the organisations current culture — Sahota takes no prisoners in his suggestion to stop doing this, to stop what he calls “accidental transformations” — forcing agile into a company whose culture is simply not ready for it.

“In my experience, many Agile change agents have done our industry a disservice by unwittingly undertaking a transformation without full buy-in or understanding of the organizational consequences.” — Michael Sahota

Perhaps he’s right, I’ve often felt like I was trying to jam a square peg into a round hole — rather we should look for that round peg? but what is it? Because it’s not agile.

Sahota suggests adopting only tools and practices (even if they aren’t from the agile family) which are compatible with their existing culture and only if/when their culture is ready should you start to bring the agile values and mindset into the picture. This feels a lot like working with where the org sits on the Fogg Behavior Model, no point in pushing something like ‘being agile’ if it’s on the wrong side of the change curve because it’s just going to fail.

Sahota’s focus on culture and ‘working with it’ tends to agree with the idea that only companies which are “agile friendly” will be able to successfully adopt an agile mindset.

But what if the culture is not ready, then what?

In his book, Sahota cites a number of case-studies suggesting that yes organisational change can still be successful albeit extremely hard.

One source which Sahota references is the book Leading Change by John Kotter. Kotter outlines an 8 step process to organisational change with step one being ‘Creating a Sense of Urgency’. A sense of urgency has interesting parallels to the motivation axis on the Fogg Behavior Model — is your motivation high enough? Is your sense of urgency for the change giving you a high enough level of motivation to keep you on the success-side of the curve?

“Ken Schwaber spoke of companies that were in really desperate situations (e.g. company survival) as good candidates for Scrum adoption since they had nothing to lose. It is clear in such circumstances that the first step — a sense of urgency — would be fully satisfied.” — Michael Sahota

Even more thought-provoking is that step four of the Kotter change process is ‘Enlisting a Volunteer Army’ — whereas Kotter puts it “Large-scale change can only occur when massive numbers of people rally around a common opportunity.” — this again has compelling parallels to the importance of critical mass reinforcing the idea that change alone is not enough, rather getting enough people to change is.

So perhaps change is only successful when both motivation and critical mass are satisfied.

If so, it would perhaps suggest that the only hope for large-traditional organisations who have had decades of building anti-agile habits would be to fire and rehire the majority of the organisation — an extreme thought — and one which doesn’t sit well with me, as firing people in the name of change usually does nothing but build a negative connotation and further resistance — but it could very well perhaps be the terrible truth for successfully changing these traditional organisations.

On that notion, Sahota actually shares a case study in his book where GM did exactly that — they fired the majority of their middle management team and replaced them. As a result, they were apparently successful in changing their culture. Intriguing, but perhaps the exception and not the rule.

Check out the Corporate Rebels if you haven’t heard of them already! (Photo by Robert Anasch on Unsplash)However to rebuttal the notion of mass-scale firing, I recently read a case study from the Corporate Rebels blog — if you don’t know about them and haven’t read their stuff I suggest you do! — the case study was around the consultancy K2K Emocionando and their radical approach to organisational transformation. An approach which hasn’t changed for over 20 years, it was inspiring to see that they worked both the motivation and critical mass angles all without firing a single person!

As the Corporate Rebels case study explores, the consultancy K2K starts any transformation much like Sahota suggests, with 100% buy-in from the CEO — no complete buy-in, no start, it’s as simple as that for them. This buy-in is not just a verbal one, it is something that is backed with action. K2K require agreement from the CEO that the change comes first, this means that they require the CEO to agree that they can be replaced at any time by either K2K or another person in the organisation if K2K deem it necessary — now that’s radical! — and if you don’t believe that they’ll follow through on that promise, they apparently have on more than one occasions!

They require a 100% buy-in from the owners of the organization and require them to commit to their change process. If not, they don’t even bother to start. — Corporate Rebels NER case study

Second, they make the CEO agree that no one gets fired — this is core to their values and the way they approach transformation — but what about all that stuff on critical mass if they are not going to fire anyone? Is it not still important? K2K’s radical approach to transformations is not absent of critical mass, rather on the contrary their approach hinders on obtaining critical mass, which is step three.

K2K next step in the process is to get the company to close-up-shop for 2 full days where they get everyone together and explain the change in detail. At the end of the two days they conduct an anonymous vote — K2K require over 80% of the employees to vote yes to the change otherwise it again is a no go for the change — 80% sounds like critical mass to me.

Interestingly Kotter put’s a similar benchmark against his “sense of urgency” step, stating that when over “75% of a company’s management is honestly convinced that business-as-usual is totally unacceptable” is when a sense of urgency is high enough for successful change.

Complete buy-in (motivation) and now critical mass, again reinforcing the idea that the two aren’t mutually exclusive when it comes to large-scale change. Empirically, K2K’s numbers speak for themselves “In total, K2K has intervened in 51 organizations, finalizing the entire transformation process in 31 of them.”

All this starts to make me draw the hypothesis that perhaps transformations should be similar to K2K’s approach — only when critical mass and a high enough level of motivation is achieved should an organisation embark on a transformation, otherwise they are likely setting themselves up for failure.

“No motivation + no critical mass = no transformation“ — a developing theory

K2K are not alone either.

Jared Spool’s company UIE share a similar approach, although for UX and not as extreme, their approach is similar in regards to only taking on work where they have satisfied a similar criteria. As Jared shares on UIE’s blog, their company policy is to only take on work when there is complete buy-in — no buy-in, no go, just like K2K.

“As a policy here at UIE, we only take on work we can guarantee results from. I know from experience that I have no chance in hell to convince any executives of anything, so I politely decline the gig. […] Our success has always come from projects where the client team, including the senior management, already understood the value of great user experiences. I haven’t convinced them because they didn’t need convincing.”

So perhaps there is hope after all, but only for those who want it bad enough.

Photo by Javier García on UnsplashBut what about the x-axis of the Fogg Behavior Model? What about influencing the barrier to change?

So far it would suggest that everyone has looked to the y-axis, the motivation side of the equation. Perhaps this is because they subconsciously believe that the barrier is fixed — change is hard and it’s not going to suddenly become any easier…I’m not sure but I think this deserves further exploration.

I often find as coaches we try to influence both angles — we try to increase motivation by helping to realise the value, whilst also focusing on breaking things down into digestible chunks not to overwhelm them and keep the barrier as low as possible — baby steps right? But even after doing so, for many, we still seem to inevitably hit a ceiling — perhaps we can influence it, but only so much.

“You can take a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink” — proverb

So where does that leave us?

Not sure about you, but I’m becoming less and less convinced that our current approach to transformation is working. Einstein said that the definition of insanity was doing the same thing over again and expecting different results — and I’m fast becoming convinced that agile transformations are becoming the definition of insanity!

Motivation is a crucial component to personal change, especially when the barrier to change is quite high. But when applying this to the context of organisational change, you are but changing one individual in a very large pool of people. This is where critical mass becomes just as pertinent, as there needs to be enough people to adopt the change to perpetuate the rest of the organisation too — without it you are left to be like those 300 brave Spartans against a hundred thousand Persians — you may put up a good fight, but defeat is inevitable.

So, perhaps Michael Sahota, UIE and K2K (among others) have it right, don’t take on any transformation where their level of motivation or critical mass are not sufficient enough. Perhaps as an agile community we need to get better at saying no to these kinds of doomed-transformations as it’s only doing the community harm.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this topic!

“Consider how hard it is to change yourself and you’ll understand what little chance you have in trying to change others. ” — Benjamin Franklin

References

IBM Blog — 84% of Companies Fail at Digital Transformation by Judy List (February 23, 2017)

Spikes and Stories — But Why Is It So (Fr)Agile? by Tanner (July 3, 2019)

Business Insider — The average iPhone is unlocked 80 times per day by Kif Lewwing (April 19, 2016)

Wikipedia — Scientific Management

MIT News — How the brain controls our habits by Anne Trafton (October 29, 2012)

Fogg Behavior Model by Dr BJ Fogg

Ron Jeffries — Dark Scrum (September 8, 2016)

Wikipedia — Critical Mass (sociodynamics)

Michael Sahota — An Agile Adoption and Transformation Survival Guide: Working with Organizational Culture (2012)

John Kotter — Leading Change: An Action Plan from the World’s Foremost Expert on Business Leadership (January 1, 1988)

Corporate Rebels — A RADICAL AND PROVEN APPROACH TO SELF-MANAGEMENT (July 26, 2017)

HBR — Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail by John Kotter (May, 1995)

UIE Blog — Why I can’t convince executives to invest in UX (and neither can you) by Jared Spool (June 8, 2011)

Whenever you're ready, I can help you in 4 ways:

Level up your craft with self-paced deep dive courses on specific topics such as Prioritisation, Stakeholder Management and many more.

More free content on Youtube. Subscribe to Product Pathways Youtube channel for regular videos on product and business.

1:1 Coaching/Mentoring: I work with product people and founders through 1 hour virtual sessions where I help them overcome challenges.

Private Workshops and Training: I frequently run private workshops and tailored training courses for product teams globally. Get in touch to talk about your unique training needs.