A Product Strategy is NOT a Vision and Roadmap

You have a strategy AND a roadmap, they’re two different things.

Photo by Maarten van den Heuvel on UnsplashOften I hear that roadmaps are part of your strategy layer. I’ve for many years struggled with this notion. Rather to me, they are a translation layer that sits between your strategy and your day to day work.

One google of the term ‘Product Strategy’ and you’ll find a dozen articles all stating that your Product Strategy is your “Product Vision and Roadmap” — this is both incorrect and misleading.

It’s, therefore, no surprise that so few companies and Product Managers have actual strategies defined — this leads to all kinds of finger-pointing, such as the common “prioritisation problem”.

Rather a strategy is something different entirely.

A roadmap is more akin to a plan. It details how you intend to achieve your strategy and/or goals — but it cannot replace having a strategy.

Strategy is a more elusive thing, and even more so in the Product Management space when you’re told you need to come up with a Product Strategy or be more strategic… but what exactly does that mean?

I recently jumped on a Linkedin live with Lisa Mo Wagner and the first question she asked me was to define strategy.

I define strategy (heavily influenced by the works of Roger L. Martin and ‘Playing the Win’) as “a set of choices”.

Strategy = a set of choices

These are choices to do something, to be something, etc. And every time you make a choice to do/be/etc something, you are also making a decision NOT to be or do something.

That’s all that strategy is, a set of choices.

And once those choices are made then they end up on a plan or roadmap.

But that’s of course not very tangible. It’s hard to visualise what exactly that is and means. This is one of the reasons why I believe we so often demote strategy down to a roadmap or some kind of plan — when it is not.

So what is a ‘Plan’ then?

Where strategy plays in the realm of the unknown, plans on the other hand, try to bring certainty and order to the chaos.

Plans operate in an entirely different domain — as Mike Tyson famously said, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Think about strategy as how you’re going to deal with being punched in the mouth — are you going to punch back, kick, protect yourself, run away? What are the set of key choices that will guide future decisions? Are you a fighter or no? Do you want to be known as one or no?

This is part of the art of strategic thinking, dealing with the inherent uncertainty of building products, companies and predicting future trends.

As Mike Tyson famously said, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth”…think about strategy as how you’re going to deal with being punched in the mouth.

Confusing the two, ‘strategy’ and ‘planning’ is a common mistake.

A plan is quite simple. It is the detailed steps of how you are going to achieve something.

Plan, noun;

“a detailed proposal for doing or achieving something.”

Your roadmap is a form of plan. Your sprint plan, the way you intend to perform a release, etc are all plans.

None of these are your strategy.

They break down detailed steps to bring clarity and outline the near term steps to achieving your goals or aspects of your strategy.

“Planning typically isn’t explicit about what the organization chooses not to do and why. It does not question assumptions…Mistaking planning for strategy is a common trap.” — Roger L. Martin

What does a Strategy look like then?

I think we’re all clear on plans, strategies however are more allusive.

There is no magical line in your org chart where strategy begins — the “decision-makers” and “executors” dichotomy is a fallacy.

Rather I see strategy as a spectrum. Every single person in the organisation are making choices (strategic decisions) all the time, just at varying levels.

There is no magical line in your org chart where strategy begins — the “decision-makers” and “executors” dichotomy is a fallacy.

For example, are you making a decision on where the company should acquire another company? That’s a pretty big choice. As opposed to making a decision to write a line of code a certain way or to put a button in a specific spot on the screen. These are still choices. Just decisions on a smaller scale with a smaller impact.

The difference as you become more senior is not that you suddenly become ‘more strategic’, rather to me it’s the fact that you now make bigger decisions, with greater impact and therefore take on more responsibility.

Perhaps this is becoming more ‘strategic’, but I view it more as further developing your strategic acumen, not that you weren’t strategic before.

You’re just operating at a different scale — like going from playing the guitar at home alone to playing at a professional level in front of a live audience as part of the symphony orchestra.

So rather than thinking of strategy vs tactics as one-vs-the-other, consider it as a continuum, from big hairy choices to small ones, with varying degrees of impact.

(As a note, strategic alignment therefore, is aligning all the 100s and 1000s of decisions and choices being made across the organisation towards a common direction. Of course, easier said than done.)

So to help you turn something messy, unclear and intangible into something a bit more ‘real’ let me give you some examples.

The output of a strategy, like a Product Strategy, is really just a documented set of choices and the context that lead you to those choices.

What choices you make, what information you include and how you structure it is all dependent on your product, company, and context.

But if you need further guidance and clarity on this, here are some examples (I also dive deeper into this topic in this blog):

‘Playing to Win’ by Roger L. Martin1) Roger L Martin would define strategy as answering these 5 questions:

1. What are our broad aspirations for our organization & the concrete goals against which we can measure our progress?

2. Across the potential field available to us, where will we choose to play and not play?

3. In our chosen place to play, how will we choose to win against the competitors there?

4. What capabilities are necessary to build and maintain to win in our chosen manner?

5. What management systems are necessary to operate to build and maintain the key capabilities?

— Robert L Martin, Five Questions to Build a Strategy, HBR

A simple way to frame your strategy. A set of 5 questions that detail different layers of choices, from what your overall aspiration is to what the necessary capabilities and systems are needed to support getting there.

As a note, Jeff Gothelf also added an additional question of “How will you know you’ve won? (your Key Result)”. I highly encourage adding this in. Measuring success and whether you are heading in the right direction is paramount to identifying when your strategy needs to adjust or change.

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash2) Another example is the Amazon 6 pagers:

Introduction — This needs to set up precisely what the material is going to cover and to inherently state the general direction of where the document plans on going.

Goals — List right up front what the metrics for success are so we can use them as a lens to see the remaining document through.

Tenets — This is a very Amazon thing where every action has some clearly define north star. There are a lot of ways to word these. Generally, they are inspirational pillars that the rest of the plan sits on top of (go with me on this one).

State of the business — This section is another important one. You need to inform the reader of the current state of the business. There needs to be a lot of detail here, which sets up the points to compare against in the next section.

Lessons learned — Amazon is big on data. This section will outline the current state of the business and its influence over creating the goals you need to achieve. It should be a detailed enough snapshot to give the reader all of the data they need to understand the positive and negatives activities in the prior period.

Strategic priorities — This is the meat of the document and lays out the plan, how to execute it, and should match up to achieving the goals stated at the top of the document.

— Jesse Freeman, The Anatomy of an Amazon 6-pager

Popularised by Amazon — and the ‘Amazonian way’ — the amazon 6 pager is a robust way to structure a product, feature, or other strategies.

It looks to take a series of inputs — tenets, the current state of the business and data — to look to detail the beliefs, interpretation of data and assumptions you are making in order to determine why we should go in a certain direction over another.

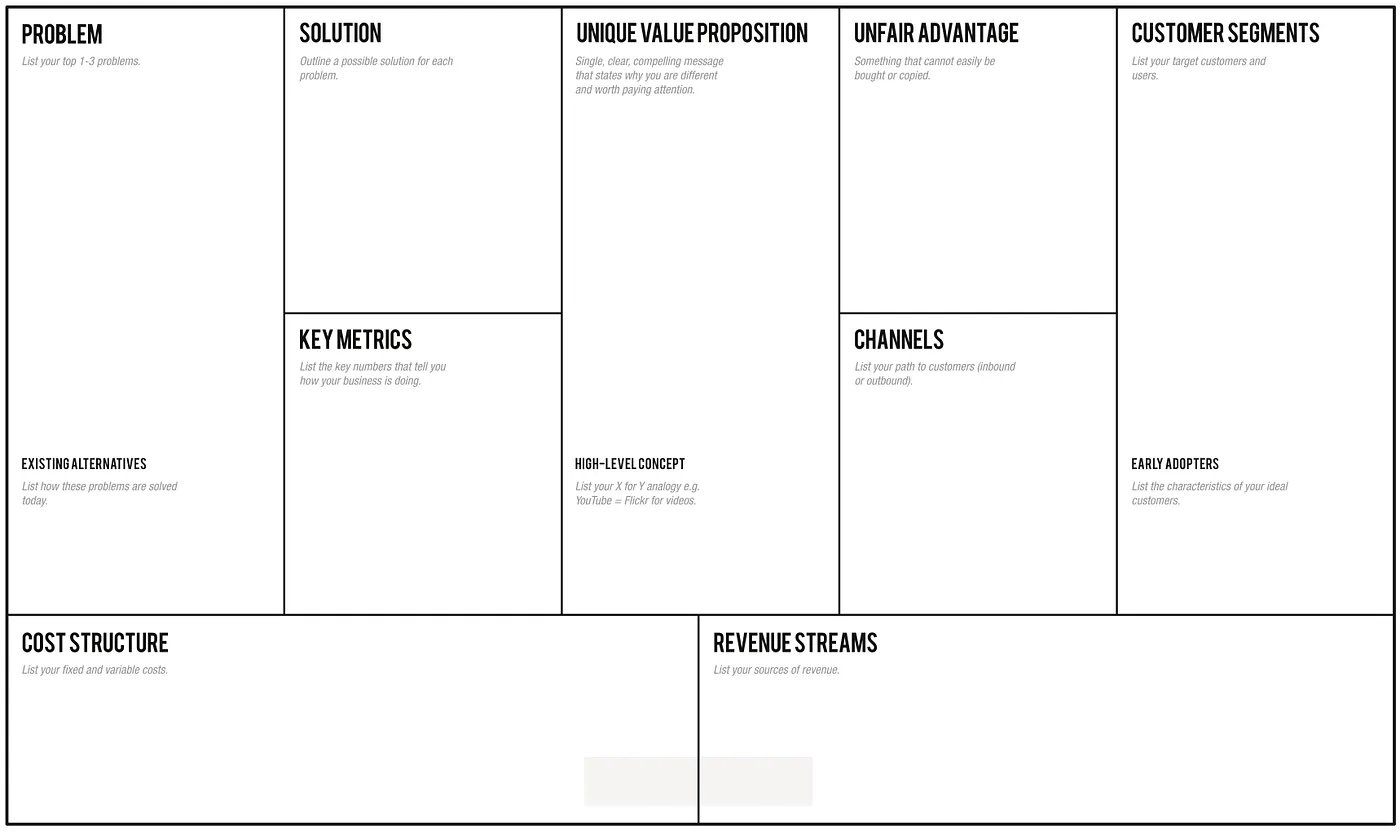

3) Even a Lean Canvas is a form of strategy:

Problem — whats the problem you’re trying to solve? Why is it so important?

Solution — what is the postential solutions?

Unique Value Proposition — What makes this different from other alternatives and why should you pay for it?

Unfair Advantage — What’s your ‘moat’? What’s the thing that is hard to copy or buy?

Channels — how are customers going to find out about it? How are you going to distribute it? etc.

Customer Segments — Who are your ideal customers? What are the characteristics of your early adopters?

Key Metrics — What are your key measure of success? How do you know if you’re winning?

Cost Structure — What are your costs? How are you going to fund this? etc.

Revenue Streams — What are your sources of revenue? How are you going to make this viable and sustainable?

Even one-pagers are a simple way to frame your strategy. They look to detail specific choices around the problem you are trying to solve, the value proposition, the distribution channels, customer segments, cost and revenue structures — these are all choices to target a specific persona, generate revenue a certain way, etc.

Photo by Mollie Sivaram on Unsplash4) Netflix DHM model from Gibson Biddle

Delight Customers

Hard to copy advantage

Margin-enhancing

The DHM model from Gibson Biddle is another simple example for framing a strategy. Answer three questions — what choices are you going to make to delight your customers, what choices will you make to have a ‘hard to copy advantage’ and what ways are you going to increase your margin — aka what sustainable business model are you going to use?

Photo by Barn Images on Unsplash5) Craft your own (example)

State of the Market: What is the data and research telling us, who are our target market segments, who are our direct and indirect competiors, how are they posistioning in the market, where do we belive they are heading, what assumptions are we making about the market and what beliefs do we have about it, etc…

State of the Business: State of the business, what the data is telling us from how we are performing, what assumptions are we making about the business currently, what are our current goals and business strategy?

State of the Product: What our is current aspiration, what is our positioning in the market, how are we performing, what is our core value proposition, etc…

Product Principles: what are our key guiding principles for the product — what are we and what are we not?

Strategic Theme #1: first strategic priority, what is it, why do we believe we should do it, how does it support the business strategy/goals and what are the OKRs for it.

Strategic Theme #2:

Strategic Theme #…:

Pricing and business model: How are we going to price the product, what’s our revenue model, how are we choosing to build a sustainable business model?

Appendix: any other relevant materials, data, research, insights, roadmap, etc.

This is a product strategy template I helped a client with. We decided to come up with our own format based on what we believed was relevant to their context and what would best resonate with the stakeholders in their organisation.

Each section breaks down into a number of sub-headings but as you can see the format is loose but structured. It’s comprehensive and provides depth to the conversation without going into the finite details of how exactly you intend to execute it.

But, what’s really important is ‘how’, not the ‘what’

Regardless of the format, your strategy details a set of choices. Choices to do something, be something, go in a certain direction, etc.

What those exact details are will depend on your product, context and organisation.

However, more important than the format itself is your process and ability to inspect and adapt over time.

Because no one can predict the future (not that I know of at least!) making key choices — your strategy — is inherently uncertain. This means that how you come to your strategy in the first place is crucial as well as your ability to adapt to new information as it presents itself.

It’s no surprise that making wild guesses is not a smart way to go about crafting your strategy. But that’s often how I see companies operating. Their leadership team lock themselves in a room every 3 to 12 months and they appear after 2 days offsite with a “strategy”.

Rather the best strategies are based on data and informed by research.

This research looks different from the typical customer research you’re probably used to. Rather, it’s investigating the market, your competitors in-depth, their positioning, doing interviews and resonance testing on alternative value propositions, pricing and financial modelling, etc.

Using information to try and get your strategy in a good shape to begin with is the first step, but responding to new information and adapting is second.

Short of inventing time travel or peering into a crystal ball, at best your strategy is an educated guess. This isn’t a bad thing, this is why strategy is so hard. But what it does mean is that strategies are emergent.

Over time you’re are going learn more, get new information, validate assumptions, be wrong in others, etc. How you respond to that becomes critical.

This is where setting a cadence — perhaps time every quarter (at the least) — to review the past 90 days, review your strategy and make necessary amendments for the next 90 days is necessary.

Finally be comfortable with the fact that your strategy is going to change, that you don’t have all the answers and things will be emergent.

But remember that this doesn’t excuse you from doing the work and gathering the right inputs — it’s not an excuse to swing blindly into the dark — do the research and make sure your strategy is informed by data.

Need help with creating a clear and effective Product Strategy (or other aspects of Product Management)?

I can help in 4 ways::

Level up your craft with self-paced deep dive courses on specific topics such as Prioritisation, Stakeholder Management and more.

1:1 Coaching/Mentoring: I work with product people and founders through 1 hour virtual sessions where I help them overcome challenges.

Private Workshops and Training: I frequently run private workshops and tailored training courses for product teams globally. Get in touch to talk about your unique training needs.