Decision Velocity & Drag

How fast is your company at making decisions? Genuinely.

Companies that move fast make decisions fast.

What takes one company a week, they do in a day. Compound that over time, and it’s a landslide.

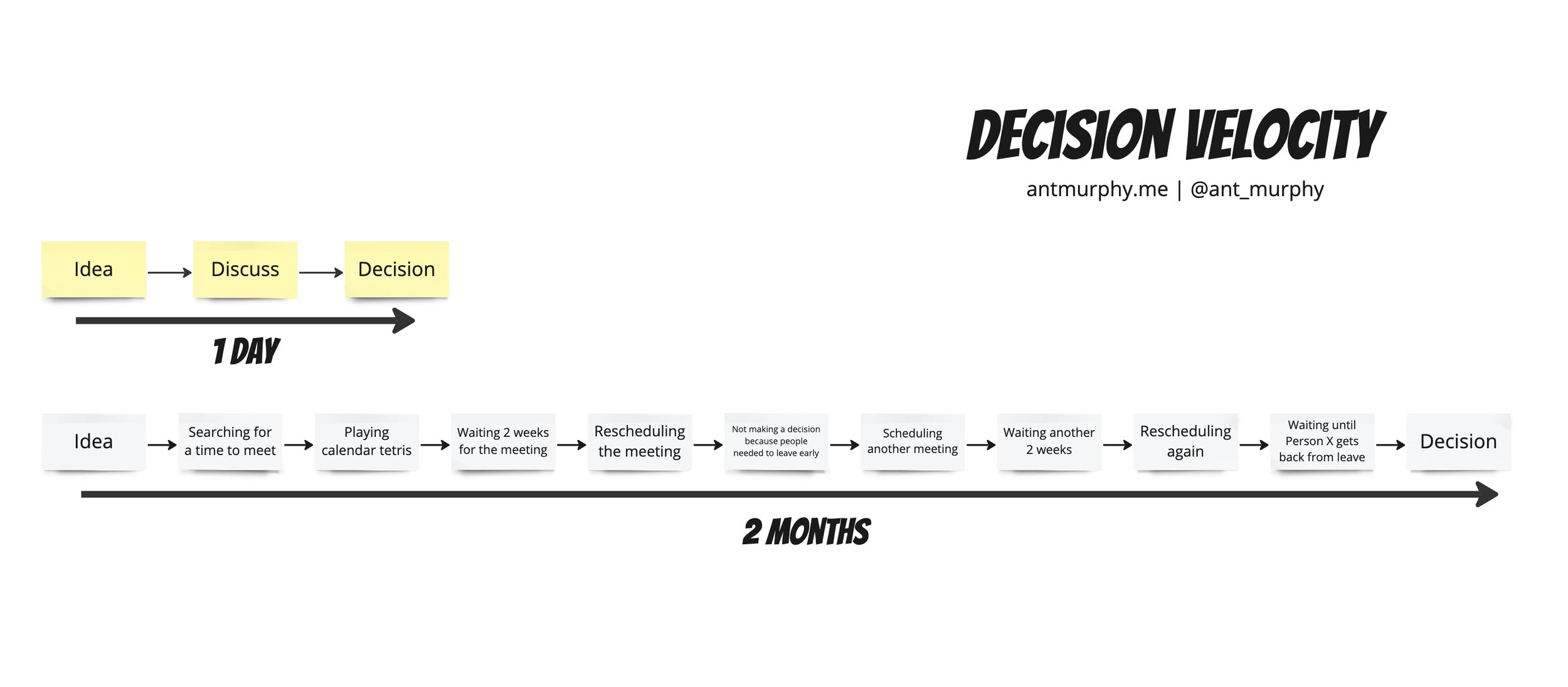

Here’s a test: If you had an idea today, how long would it take to make a decision?

End of the day? End of the week? Longer?

Let’s explore two real scenarios:

Organization A:

It’s Tuesday morning, and the VP of Product’s leadership team gathers for their weekly meeting. They just lost a key team member. They discuss the need to backfill this role and what to do in the interim with the constraints they have. They decide a workshop is needed to solution the problem.

A 2-hour workshop was scheduled for the next day with several key people.

Everyone invited was able to attend the workshop and an plan of action was the result.

Less than 24 hours had elapsed from the time the problem arised to action being taken.

Now compare this to Organization B:

Organization B has just done a routine employee engagement survey. Due to recent changes, the scores came back and they weren’t good.

The leadership realized that the scores were poor enough that action needed to be taken. A meeting was scheduled to discuss. However, since everyone was so busy, playing calendar-tetris meant that the meeting was scheduled for following week.

The day before the meeting, it gets rescheduled. Conflicts have come up, and 2 key people no longer can make it.

Another week passed, and the meeting finally happens; however, they could only find 30 minutes when everyone was availiable (with all the back-to-back meetings) and half an hour was not nearly long enough to work through the problem properly.

So, another meeting is scheduled. And another week elapses.

The team meet again. This time they assign work to a ‘working group’ that working group is to report back in 2 weeks time.

2 weeks later, the working group report back with a set of recommendations. However, given the sensitive nature of the recommendations, they believe they must first run it by more people for approval.

Another two meetings are set up to run through the proposal.

….and you get the point. (I think they’re still working on that decision today - kidding!)

Where do you sit on the spectrum from Organisation A to Organisation B? While Organizations A and B aren’t competitors, you can imagine if they were.

Even if Organisation B has the dominant market position today, do you think that they will keep it in 5? or 10 years’ time?

While decision velocity isn’t everything, speed is a key component to success in almost any field.

If you can learn faster, improve faster, deliver faster, get feedback faster, and act on the feedback faster than anyone else then no gap is impossible to close. And if you’re already ahead, then no one can catch up!

Many well-known leaders have spoken about the importance of fast decisions.

Jeff Bezos, in fact, wrote a whole chapter on this topic in his 2016 ‘Letter to Shareholders (it’s a good read, so I thought I’d include it below).

High-Velocity Decision Making

Day 2 companies make high-quality decisions, but they make high-quality decisions slowly. To keep the energy and dynamism of Day 1, you have to somehow make high-quality, high-velocity decisions. Easy for start-ups and very challenging for large organizations. The senior team at Amazon is determined to keep our decision-making velocity high. Speed matters in business – plus a high-velocity decision making environment is more fun too. We don’t know all the answers, but here are some thoughts.

First, never use a one-size-fits-all decision-making process. Many decisions are reversible, two-way doors. Those decisions can use a light-weight process. For those, so what if you’re wrong? I wrote about this in more detail in last year’s letter.

Second, most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you’re probably being slow. Plus, either way, you need to be good at quickly recognizing and correcting bad decisions. If you’re good at course correcting, being wrong may be less costly than you think, whereas being slow is going to be expensive for sure.

Third, use the phrase “disagree and commit.” This phrase will save a lot of time. If you have conviction on a particular direction even though there’s no consensus, it’s helpful to say, “Look, I know we disagree on this but will you gamble with me on it? Disagree and commit?” By the time you’re at this point, no one can know the answer for sure, and you’ll probably get a quick yes.

This isn’t one way. If you’re the boss, you should do this too. I disagree and commit all the time. We recently greenlit a particular Amazon Studios original. I told the team my view: debatable whether it would be interesting enough, complicated to produce, the business terms aren’t that good, and we have lots of other opportunities. They had a completely different opinion and wanted to go ahead. I wrote back right away with “I disagree and commit and hope it becomes the most watched thing we’ve ever made.” Consider how much slower this decision cycle would have been if the team had actually had to convince me rather than simply get my commitment.

Note what this example is not: it’s not me thinking to myself “well, these guys are wrong and missing the point, but this isn’t worth me chasing.” It’s a genuine disagreement of opinion, a candid expression of my view, a chance for the team to weigh my view, and a quick, sincere commitment to go their way. And given that this team has already brought home 11 Emmys, 6 Golden Globes, and 3 Oscars, I’m just glad they let me in the room at all!

Fourth, recognize true misalignment issues early and escalate them immediately. Sometimes teams have different objectives and fundamentally different views. They are not aligned. No amount of discussion, no number of meetings will resolve that deep misalignment. Without escalation, the default dispute resolution mechanism for this scenario is exhaustion. Whoever has more stamina carries the decision.

I’ve seen many examples of sincere misalignment at Amazon over the years. When we decided to invite third party sellers to compete directly against us on our own product detail pages – that was a big one. Many smart, well-intentioned Amazonians were simply not at all aligned with the direction. The big decision set up hundreds of smaller decisions, many of which needed to be escalated to the senior team.

“You’ve worn me down” is an awful decision-making process. It’s slow and de-energizing. Go for quick escalation instead – it’s better.

So, have you settled only for decision quality, or are you mindful of decision velocity too? Are the world’s trends tailwinds for you? Are you falling prey to proxies, or do they serve you? And most important of all, are you delighting customers? We can have the scope and capabilities of a large company and the spirit and heart of a small one. But we have to choose it.

- Jeff Bezos, 2016 Letter to Shareholders

Decision Drag

Opposing high decision velocity is decision drag.

Decision drag comes in all shapes and sizes, but the most common things I observe in the companies I advise are:

High WIP (Work-in-Progress)/Utilisation

The Optimisation Problem Trap

Perfectionism

Treating two-way-door decisions as one-way

High WIP

High work-in-progress is the number 1 killer of decision velocity in my experience.

It was the key culprit in Organisation B. There was so little slack* in the system that the earliest a workshop or meeting could be scheduled was a week away.

High WIP doesn’t just hurt decision velocity, it’s bad for your people and customers too! High WIP also creates decision drag through context switching.

I’ve seen organizations where they’re trying to work on a problem, but everyone in the ‘working group’ is part-time. This is just one of seven other things they’re juggling. In the end, all seven drag on.

Optimisation Problem Trap

I’ve written about the Optimisation Problem Trap before, but in a nutshell, ‘The optimization problem’ is the conundrum of finding the best possible solution out of all feasible solutions.

Sounds like a good thing, right? But it can quickly go from solving the ‘Optimization Problem’ to a trap.

Consider the following scenario:

Person A raises that they have this problem and they're going to try X.

Person B sees similarities with what another team is going. They are excited by the opportunity to optimize. Person B sets up a meeting to consolidate approaches and decide on a consistent approach across the org.

Person A and B both meet, perhaps half a dozen times over the following weeks. They map out all the possibilities, differences in context, edge cases, etc… in the end, they spend weeks trying to find an approach that suits both their contexts and all future needs.

Months go by and they’re still working on a consolidated approach. However, much of the market and each team’s needs have changed. They’re chasing a moving target.

Sound familiar?

In this scenario, rather than high WIP causing decision drag, it’s the desire to have the perfect solution.

I often see the Optimisation Problem Trap manifest itself in trying to avoid duplication, avoid inconsistency or not wanting to ‘reinvent the wheel’.

We then rationalize that perhaps other teams or departments have faced this problem before or that they might in the future, so we need to solve it for their context as well. This quickly snowballs. We then need to involve more people and gather more inputs. Eventually, the problem space expands, and the solution becomes overly complex. Suddenly, we find ourselves sitting in a workshop with a ‘cast of 1000s’, and we’re no further from where we were a couple of days (or weeks) ago.

Perfectionism

Much like the Optimisation Problem Trap, seeking the perfect answer or even the perfect data is the antithesis of quick decisions.

Now, of course, there’s the opposite extreme, where we make really fast but terrible decisions in the absence of data. So some decision drag is a good thing.

Jeff Bezos, in his shareholders letter above, talks about making decisions with ~70% of the information rather than waiting for 90%. While subjective and we will never know when we’re at 70% or not, I think it’s a good guide.

I once heard that:

“an 80% decision on time is better than a perfect decision too late.”

This hit home for me because a perfect decision too late is useless, regardless of how perfect it is.

Treating two-way-door decisions as one-way

The desire for perfect decisions often comes from treating two-way-door decisions as one-way, as Jeff Bezos alluded to in his letter to shareholders.

Two-way-door decisions are reversible. When you realize it was a mistake, you can come back through the door. However, one-way-door decisions are not.

Jeff Bezos has been known to talk at length about one vs two-way door decisions and is quick to state that most decisions we make are reversible, yet companies often treat them as not.

A question I ask in my training or coaching is to think of decisions that aren’t reversible. Often, I get responses on major life decisions like taking a mortgage to buy a house or getting married. But if you really unpack them, they are reversible - albeit difficult - but you can always sell the house or file for bankruptcy, and get divorced.

In fact, when you really think about it, there are very few non-reversible decisions. I can only really think of a couple of decisions in my whole life that were genuinely irreversible:

Becoming a father one. Yep no going back there!

Going skydiving and taking that final step out of the plane. Once you’re out, gravity wins!

Joining the military (not least for the minimum service period)

But besides those, everything else was reversible to some extent.

I’ve found this framing to be a hallmark of a high decision velocity company.

They recognize that most decisions are indeed two-way-door ones, and therefore, are not afraid to be wrong.

This framing also helps to fend off decision drag, like perfectionism and the optimization problem becoming a trap.

However, walking through two-way doors also requires becoming good at recognizing when you’ve made a wrong turn. As well as having the mechanisms in place to quickly course correct (a high decision velocity helps here, too!).

Reflection

This is something I’ve been thinking a lot about of late. Not that I feel I’m not decisive enough; in fact, decisiveness is a trait my wife and I proudly share. As an example, we recently bought a new car, and it took us less than a week and only two trips to the dealer to make a decision. But more so in some more niche aspects - like emails.

Something my wife loves to poke fun at me about is how I over-cook emails. I have this terrible habit of writing an email, then re-writing, and then re-writing again and perhaps one more time for good measure. It could be something as simple as replying to our son’s school, yet I will proofread and re-write that damn email seven times before hitting send.

It’s a great example of decision drag and something I’m actively trying to work on.

But I thought I’d share as it’s not always the big stuff. It’s sometimes the smaller day-to-day activities that, for whatever reason, there’s drag.

Final thoughts:

How’s your decision velocity?

Are there things in your day-to-day which you’re fast at and others not so much? (like my email replies)

Are their decisions, perhaps you’re trying to make right now, that you’re treating as a one-way door decision when it’s really not?

How good are you and your organization at recognizing when you’ve made a wrong turn?

Do you have mechanisms in place to pivot quickly and course correct?

*‘slack’ imagine a rope. It’s either pulled tight or there’s some ‘slack’ (some give in the rope).

Need help with scaling your product or business? I can help in 4 ways::

Level up your craft with self-paced deep dive courses, FREE events and videos on YouTube, templates, and guides on Product Pathways.

1:1 Coaching/Mentoring: I help product people and founders overcome challenges through 1-hour virtual sessions.

Consulting and Advisory: I help companies drive better results by building effective product practices.

Private Workshops and Training: I run practical workshops and training courses for product teams globally. Get in touch to talk about your unique training needs.

Your OKRs don’t live in a vacuum.

Yet this is exactly how I see many organizations treat their OKRs.

They jump on the bandwagon and create OKRs void of any context.

Here’s what I see all the time…