The Adjacent Growth Strategy

I wanted to continue from my last post at the end of the year on ‘Niching Down’, where I introduced the Niche Canvas and touched on how it can be a great tool for thinking about growth.

So, let’s talk more about that - strategies for growing your business or product.

The Niche Canvas can be a neat tool for thinking about expanding beyond your initial 'niche’Now, a prerequisite to growing beyond your initial product is having a successful product in the first place.

The first rule of growing any business or product is to double down on what's already working first.

It can be very tempting to chase new opportunities and the curse of success opens more doors, and the opportunities behind those doors become more attractive.

I’ve talked before about how a lack of focus, patience, and persistence can kill your business. Once you’ve spread your people, resources, and mental capacity thin, you end up doing neither the new ‘shiny’ opportunity nor your core product well.

Quality slips, development slows down, churn increases, and so begins decline.

As Steve Jobs said,

“People think focus means saying yes to the thing you've got to focus on. But that's not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are.

So, let’s assume a few things to be true first. Consider these as prerequisites for expanding beyond your initial offering:

Things are stable.

You have PMF (Product-Market-Fit)

You're either exiting the growth phase or have been in growth for some time.

You’re a master of what you’re already doing. Perhaps you’re the market leader or no. 2 in your current market.

You want to grow the business or de-risk from having “all your eggs in one basket” (this is a deliberate choice)

You have the available cash flow to direct people and resources towards something new without starving your initial offering (ideally without impacting it at all)

Assuming some, if not all, of these are true, then you’re in the privileged position to consider growth through either new products or expanding into new markets.

Intro, the Product/Market Expansion Grid.

The Product/Market Expansion GridProduct/Market Expansion Grid

You’ve probably seen this before (or variations of it), but the Product/Market Expansion Grid explains that expansion can really come from only 1 of 4 places:

Growing your existing product in your current market

Expanding your current product into new markets

Creating new products for your current market

Creating new products for a new market

This matrix is also known as the Ansoff matrix. Igor Ansoff first introduced this concept in his 1957 paper called ‘Strategies for Diversification’.

The matrix is a useful tool for conceptualizing these 4 different avenues of growth, and more importantly, the risks associated with them.

One of the things that Ansoff and many others have talked about is that the further you move away from your initial product offering (in either dimension - product or market), the risk increases.

Risk increases the further you move away from your existing product and marketIn other words, expanding your current product in your current market is the lowest risk activity - and another reason why I advocate for doing that first.

That’s because it’s known. You know the market, you have existing customers who you know well, your product likely already has PMF, etc.

Now compare that to moving your product into a new market. Even if you did have PMF in the existing market, you don’t know for sure if that will be true in the new market.

Moving ever further out, you then have to develop a new product for a new market. Doing so is venturing into uncharted territory.

This is why we want to remain as close to our initial offering as possible when we expand. And the best way to do do is through adjacent products/markets.

Adjacent Growth Strategy

Many have written about leveraging adjacent markets, users, and products as a growth strategy. From the book ‘Beyond the Core’ by Chris Zook, ‘Competing on the Edge’ by Brown and Eisenhardt, and the more recently popularised Adjacent User Theory.

All share the same underlying notion that Ansoff first outlined: that the further you move beyond your core product, the risk increases. Therefore, moving into adjacent areas becomes a logical choice.

This tactic has been leveraged by companies for millennia.

Apple expanded from computers to tablets to phones and even headphones, speakers, etc.

Tesla expanded from cars to batteries and solar panels, etc.

Coca-Cola started in the USA and is now practically available in every country. Not to mention expanding into more than 500 other beverages, such as Fanta and Bacardi.

Samsung was founded in 1938 and has since gone from producing black-and-white TVs to Fridges, cooktops, and even washing machines.

Adjacent Markets

The lowest risk option is to move your current product offering into a new market - to be more precise, into an adjacent market.

Option 1: Move your current Product Offering into an Adjacent MarketAn adjacent market is a market that is similar, related, or connected to your existing market.

For example, the fitness industry has several market segments within it. If you were to produce clothes for runners, an adjacent market might be gym-goers or cyclists.

The adjacent user theory is a great tool to apply here.

“Adjacent users are users who are aware of the product, possibly tried and even used it, but for some reason, they cannot be successfully engaged users. This is typically because the current product positioning or experience has too many barriers to adoption for them.” - Adjacent User Theory by Bangaly Kaba

For example, keeping with the fitness apparel example, many people have started wearing fitness clothing day-to-day because of their comfort. This spun up a whole industry and fashion trend known as ‘athleisure wear’. In other words, fitness brands have customers who don’t actually do any fitness, but they use their products for a different use case. These users or potential users are an easy adjacent market to target and can often unlock immediate growth.

Adjacent Products

The next option you have is building adjacent products for your existing market.

The advantage of this approach is that you can leverage your existing position, marketing, brand, product offering, etc to upsell or cross-sell.

Option 2 is to build adjacent products for your existing marketHowever, it is more risky than simply expanding into new markets because it requires researching and developing a new product.

Furthermore, it’s the least diverse, as you still have all your ‘eggs in one basket’, so to speak. If the market was to enter a downturn both your products would suffer.

Finally, there’s also the (small) risk that your new product might be detrimental to your core product. If the new offering is not up to scratch, it can erode your brand and position in the market, having a flow-on effect on your other product.

The 1-Degree of Separation Rule

In the book ‘Beyond the Core’, Chris Zook talks about adjacent moves ideally having no more than 1-degree of separation from your core business or product.

Therefore, when expanding into an adjacent market or introducing a new product to your current market, you ideally want to have no more than 1-degree of separation from your existing product offering.

‘The 1 Degree of Separation Rule’ means expanding no further than 1-degree of separation from your core product/marketThis is a great test to determine if the market or product is, in fact, an adjacent one. Any more than a single degree, and it cannot be adjacent.

This doesn’t mean that you’re constrained to what is immediately adjacent. Instead, the idea of the strategy is to take smaller more incremental steps.

In other words, rather than trying to make huge leaps-and-bounds, we want to be incremental. To expand into one adjacent area and then into the next.

For example, Lululemon started in Yoga Clothing for Women. Therefore, when they moved into Yoga clothing for men and then expanded to other fitness verticals (like running or gym clothes), these were both 1-degree of separation. Whereas, leaping from women’s yoga apparel to men’s golf equipment, while both are falling within the fitness industry, there would be well more than one degree of separation.

Lululemon grew through 1-degree of separation movesIf you really apply this thinking strategically, you can begin to chart a deliberate growth path - to start in one market and deliberately expand into others.

For example, we may need to first move from Yoga clothes to fitness clothes in general, then unisex clothing, and then we can move into fitness equipment. Fitness equipment will allow us to move into electronic fitness equipment, which can then move into other spaces like even a fitness-orientated phone - and voila! Lululemon is now a tech company.

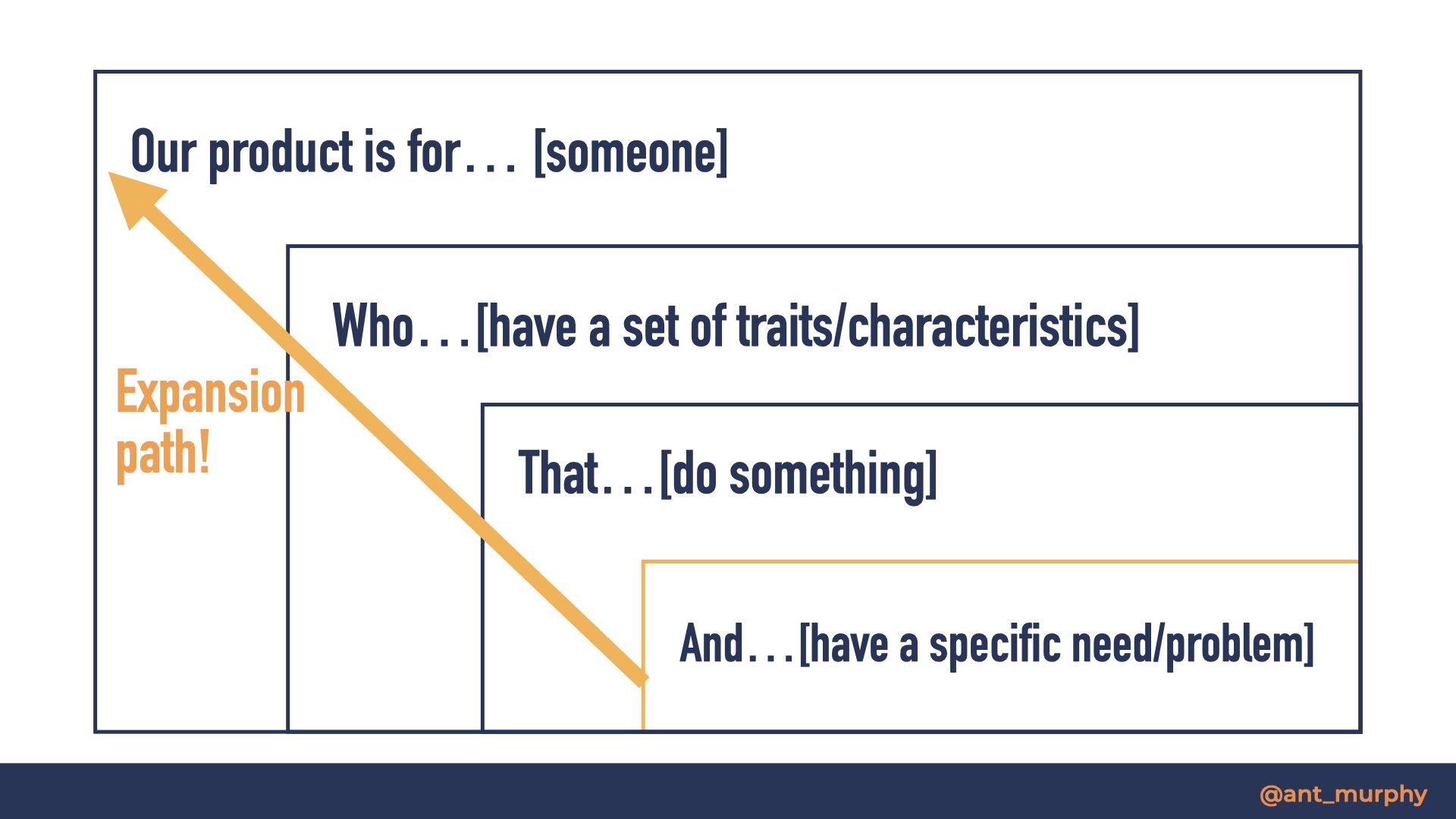

Moving into entirely new markets requires developing a deliberate expansion pathThe ‘Nice Canvas’ was designed to incorporate this thinking.

Each step in the ‘Nice Canvas’ typically represents 1-degree of separation. You wouldn’t leap from your niche to the outer box, instead you would incrementally step up through each box, one at a time.

Now, by no means is this a fool-proof strategy, nor is it the only way to grow your product and business. But this is the most dominant way companies and products expand; they look at the periphery and make incremental moves, slowly taking a bigger and bigger chunks of a market.

This strategy has its downsides, of course, namely not being able to defend against significant disruption nor helping you be the disruptor as it doesn’t promote significant innovative moves.

However, whilst major innovation does happen, it’s not how the majority of companies grow. Instead, they start narrowing and grow incrementally.

Remember to remain focused above all and refrain from expanding too early. When you do decide to expand, leverage the Adjacent Growth Strategy.

Think about your options between adjacent markets and adjacent products, and be deliberate about which moves you make. Make sure you have a larger goal in mind and you’ve charted yourself a growth path that leverages incremental steps that compound over time.

Need help with scaling your product or business? I can help in 4 ways::

Level up your craft with self-paced deep dive courses, FREE events and videos onYouTube, templates, and guides on Product Pathways.

1:1 Coaching/Mentoring: I help product people and founders overcome challenges through 1-hour virtual sessions.

Consulting and Advisory: I help companies drive better results by building effective product practices.

Private Workshops and Training: I run practical workshops and training courses for product teams globally. Get in touch to talk about your unique training needs.

Your OKRs don’t live in a vacuum.

Yet this is exactly how I see many organizations treat their OKRs.

They jump on the bandwagon and create OKRs void of any context.

Here’s what I see all the time…