Escape OKR Theatre

Hey I’m Ant and welcome to my newsletter where you will find practical lessons on building Products, Businesses and being a better Leader

You might have missed these recent posts:

- What is Product Management

- Driver + Navigator

- Great Product Managers Go Deeper

p.s. If you’re looking to grow your impact and accelerate your career, check out the Product Mentorship!

It must be OKR season!

The last couple of weeks I’ve gotten a lot of questions about OKRs (Objectives and Key Results), including one yesterday whilst writing this post… honestly if this was published I could have just sent them the link.

So let’s avoid another call. In this post I want to equip you with the different hallmarks I look for in effective OKRs so you can self-diagnose and hopefully escape OKR theatre!

Let’s get into them 👇

1. Number of OKRs

OKRs provide two key benefits from my perspective, focus and alignment.

Therefore one of the first things I look at is how many OKRs and KRs (Key Results) are there?

For KRs ideally you want to be in the 2-4 range.

Of course there are situations where it might make sense to have 6 or even more KRs for a single objective, but any OKRs with that many Key Results will stand out and immediately draw my attention.

From an OKR perspective, less is often more.

If OKRs are supposed to help with focus and alignment, having too many will obviously do the opposite.

I see this often with the companies I work with.

They have a sea of OKRs.

OKRs at every level, every department, every team and even every individual have their own OKRs.

Before you know it each team has 5+ OKRs all funnelling to them - with many competing.

It’s more noise than clarity.

As a result, I’ve now started to go more aggressive at the level.

Ideally I want to see <3 OKRs (dare I say 1x OKR even!)

As Christian Idioti, partner at Silicon Valley Product Group says:

“You want 10 teams working towards 1 goal, not 1 team with 10 goals”.

2. Measurable

It goes without saying that KRs in your OKR need to be measurable.

A great format to use that ensures your KRs are specific and measurable is writing them as “From X to Y”

e.g: KR: Increase DAU (daily active users) from average of 4,000 per day to 5,000 per day.

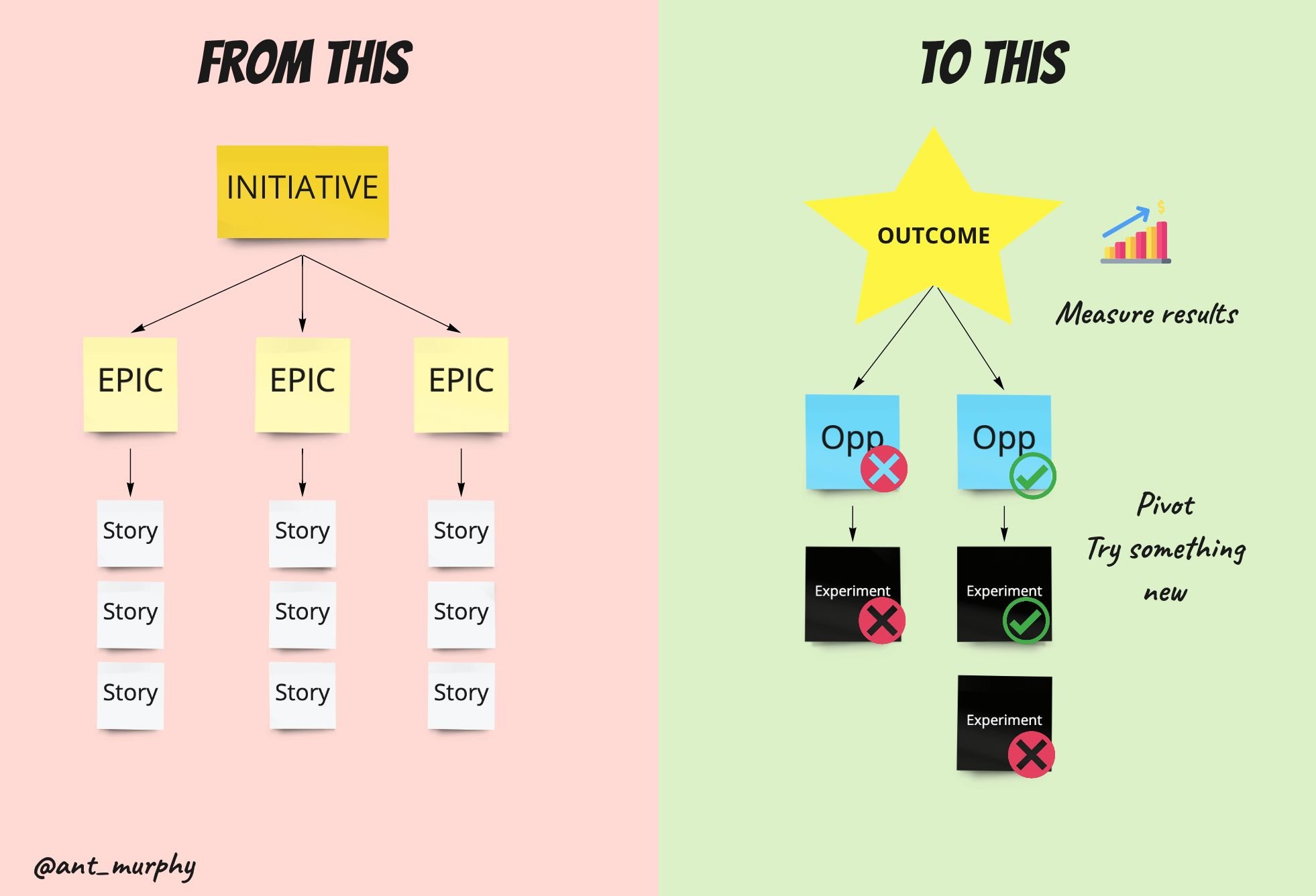

As part of measurable I’m looking to see if they’re focused on outcomes, not outputs.

One of the hard parts about outcomes is that we’re never 100% in control of them.

There might be a president who decides to introduce global tariffs that throw buyer behaviour into a spin. Or the central bank curbs spending through raising interest rates.

Or like one startup I coached, you might have a major website mention your product and suddenly get a flood of new sign ups!

Either way you’re not fully in control and that can be hard for some people to wrap their heads around and accept. Especially in a system where they might be used to being rewarded and punished based on targets.

As Goodhart’s Law states:

"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”

Therefore one of the things we need to be careful of with OKRs is the goal becoming a must hit target.

Credit: Work Chronicles

When this happens it leads to sandbagging and output orientated KRs.

And I get it, because when you’re being held to OKRs (another anti-pattern) that could mean your bonus, a promotion, your job even, then it’s only natural to make them easy targets that are in your control.

This is also why you might notice that I don’t have ‘time-bound’ in this list.

Yes your OKRs should have a time-horizon but sometimes that time horizon is arbitrary and it can often turn a goal into a target.

Instead I think about time and measurability (is that even a word?) of OKRs in two dimensions:

Direction = are we progressing in the right direction, towards the goal (directionally correct)

Speed = how fast are we moving towards the goal?

(For those physics nerds out there you’ll notice this is the two dimensions of Velocity)

Hoping to achieve an outcome by the end of the quarter is great but it’s only half the picture.

The timebox, this quarter, is the speed component.

The more important question to me is are we directionally correct?

Remember that outcomes aren’t fully in our control, meaning that there’s a chance that there might be external forces working against us.

Or in a lot of cases we were simply overly ambitious.

When we chase speed over direction we often move the goal posts.

We start to chase vanity metrics or focus too heavily at the top of the funnel.

Pushing sales at the expense of experience and retention, anyone?

Don’t sacrifice direction for speed.

3. Realistic

I can hear some of you already, but OKRs should be aspirational, that’s the point!

Yes, OKRs should be somewhat aspirational but there’s a balance between ‘a stretch’ and just outright unrealistic.

Unrealistic goals don’t motivate, they do the opposite.

In fact Professor Teresa Amabile at Harvard noted that “On days when workers have the sense they're making headway in their jobs, or when they receive support that helps them overcome obstacles, their emotions are most positive and their drive to succeed is at its peak.”

It’s the sense of progress and accomplishment that motivates and drives, not always coming up short!

Setting an OKR to double revenue this year doesn’t make it magically happen - nor realistic.

This is where strategy comes into the picture.

As Richard Rumelt put it in his book Good Strategy Bad Strategy:

“Executives who complain about "execution" problems have usually confused strategy with goal setting.”

Your OKRs should be a model of your strategy.

And a good strategy takes your context, strengths, weaknesses, constraints and everything into account.

A good strategy is realistic or as Richard Rumelt puts it; “A good strategy honestly acknowledges the challenges being faced and provides an approach to overcoming them.”

4. Cohesion

A great strategy is cohesive and since your OKRs are based on your strategy, then they too should be cohesive.

In other words they should compliment each other.

Here’s some examples:

Would chasing growth whilst cutting costs be cohesive?

Not typically.

Growth usually involves investment into research and development. It also means trying new things and we know that some bets wont work out. That’s part of the process, trying something, seeing the results and learning from them.

However, growing through increasing acquisition whilst minimising churn is cohesive.

Both (acquisition and retention) are levers for growth. Of course you could double down on one, and depending on your size that might be necessary but larger companies could do both.

The same applies for your KRs.

Do they complement or create healthy tension with each other?

Or are they disparate measurements - worse, separate problem spaces in their own right.

5. Is there an underlying model

I’ve talked a lot about strategy so far and this section could be framed as whether or not your OKRs are based on a strategy but that’s hard to action.

Instead John Cutler framed it well;

“One thing I look for are signals that they relate to some sort of enduring and persistent underlying model, or whether it is obvious they were just tacked on to existing ideas for projects. Over time, do they tell a story?”

So another way of testing whether there’s a strategy or not is whether you can see resemblance of an underlying model.

Corinna Stukan also framed this as ‘being able to connect the dots’:

“I love doing the ultimate litmus test: can people connect the dots? 😊

E.g. if a team or individual works on a certain feature / marketing or sales activity / process change etc., can they clearly articulate how this activity contributes to the broader business goals?

If OKRs are not clear, too complicated, too many, not cohesive etc. as in your list, it becomes really hard for teams to do this in my experience!”

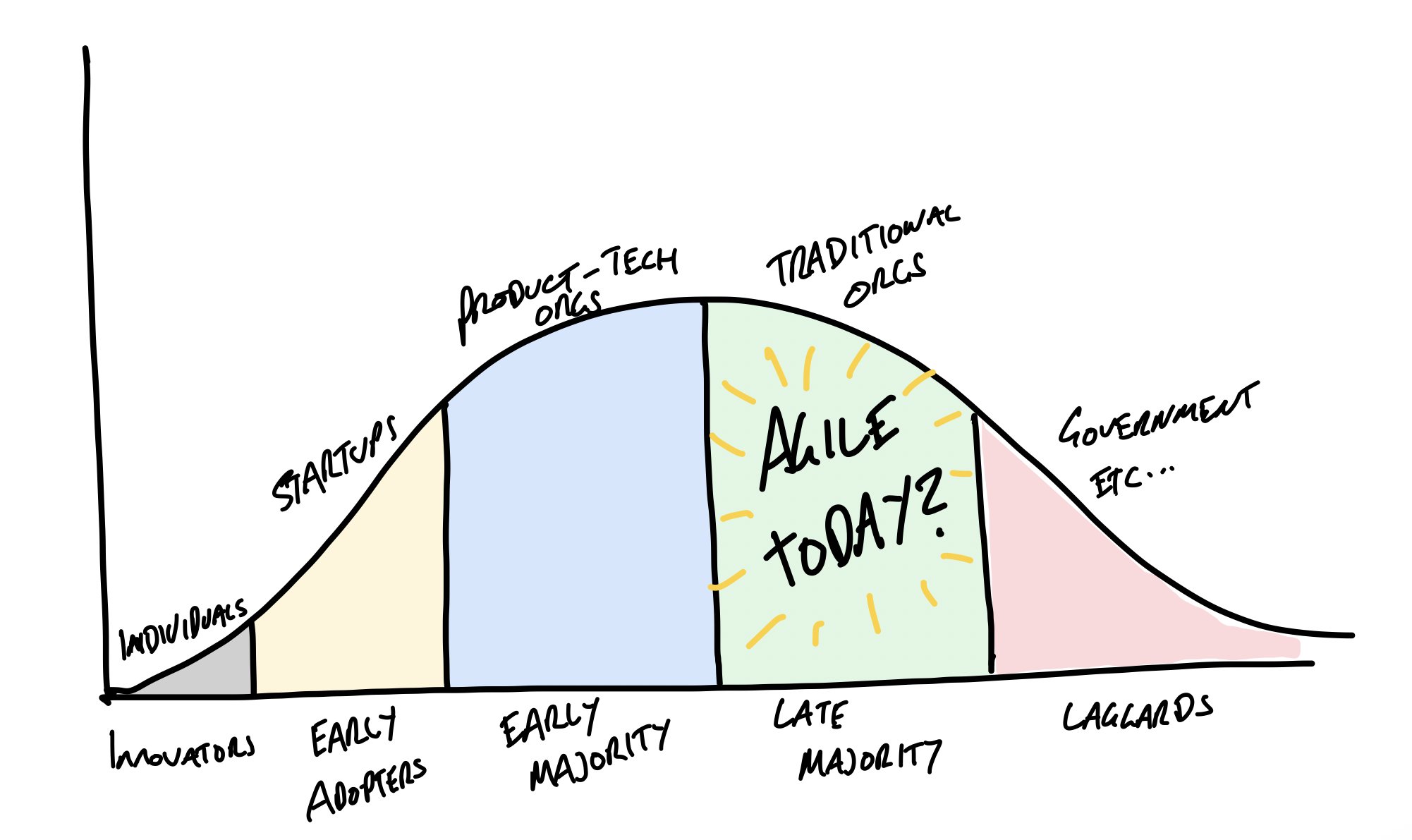

6. Cascading

OKRs should align, not cascade.

There’s a lot of reasons why cascading doesn’t work. Most companies I see who do this end up in a ‘square peg, round hole’ situation, trying to make their goals fit the org chart (rather than the other way around).

Cascading is also a signal that strategy is absent, because if it was there the chances it perfectly mirrors your org chart is low.

“Another red flag: cascading OKRs. Which tends to happen when there is no underlying model (see John's comment). Good models help to tie local action to bigger impact. No cascade needed.” - Sascha Brossmann

7. Obvious

Another simple test to apply here that overlaps with the previous points on strategy is how obvious the OKRs are.

Roger L Martin, author of Playing to Win and arguably one of the most renowned thinkers on strategy, applies this simple test:

Is the opposite stupid on its face?

In other words, is the opposite to your strategic choices (in this case OKRs) something that you would clearly NOT do?

“The opposite of filing your corporate tax returns on time is stupid on its face; but you better file your corporate tax returns on time or you are in big trouble.” - Roger L Martin

Anything that is obvious or where the ‘opposite is stupid on its face’ is likely going to be a pretty bad OKR.

“Objectives that are “well duh” when they just restate basic things that your product/service is always trying to do. Some examples being “We have a product that solves peoples problems” or “Provide a helpful service””

- Nicolas Brown

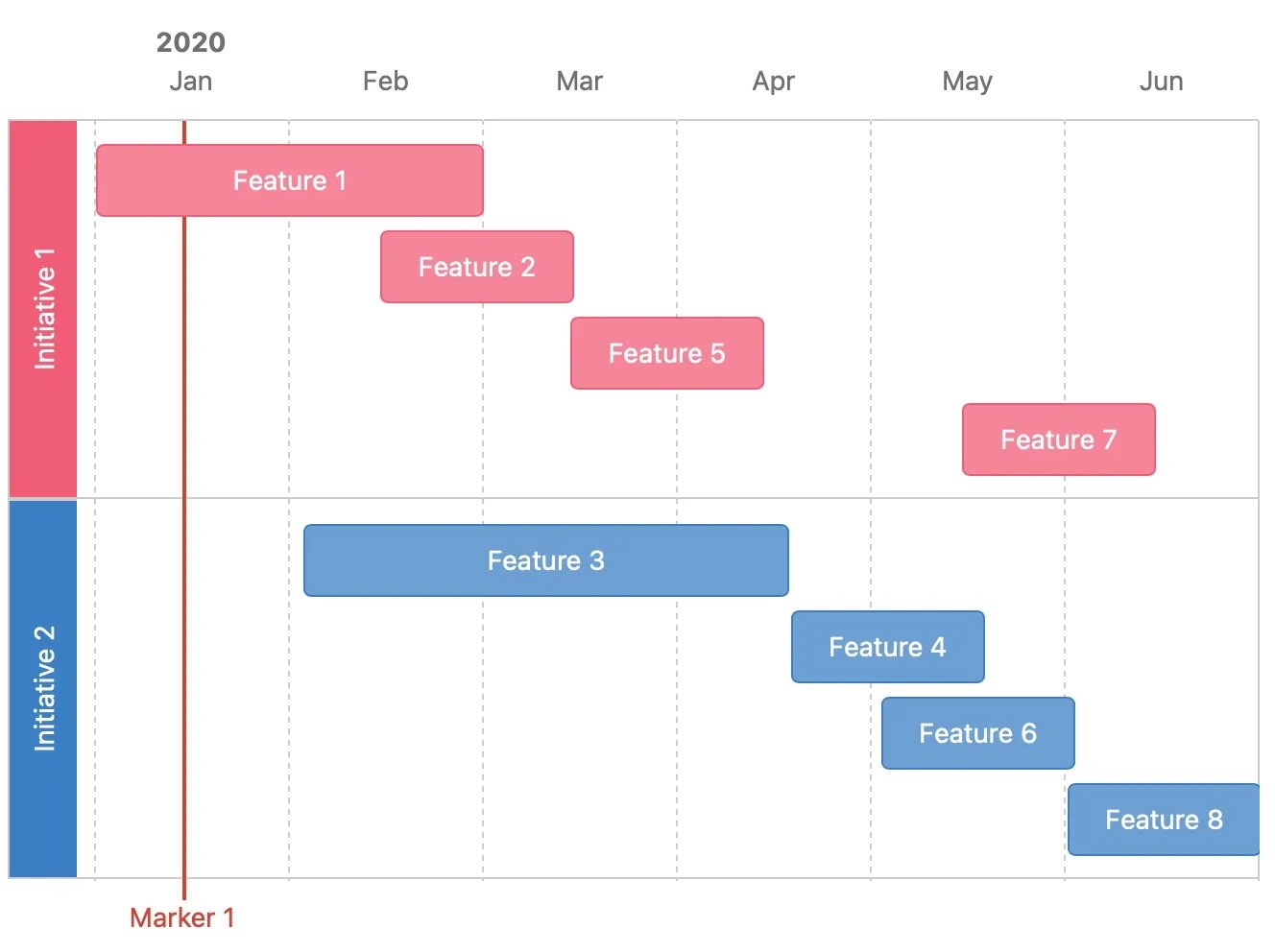

8. Leading vs Lagging indicators

These last two are a bit harder to quickly suss out but they’re worth mentioning.

There’s a danger in setting KRs that are very lagging.

‘Lagging’ meaning that it will take months, years even to see the effects.

In product (and most things) we want tight feedback loops.

The earlier I can get an indication on whether I’m heading in the right direction or not, the better.

The problem with lagging measures is that it’s a long time to know whether you’re achieving your goal or not.

Remember when I talked about speed + direction. This is the direction part, you want to know whether you’re heading in the right direction as quickly as possible so you can do something about it.

Now there’s a nuance here because depending on how you use OKRs in your organisation, you might have higher level, more lagging OKRs with lower-level, more leading OKRs that align to the lagging KRs.

In that case this would be fine.

The danger and thing to suss out is whether you have only lagging KRs and how long/short is your feedback loop?

9. Do they break down the problem space

Do your OKRs break down the problem space and provide focus?

This is something I’ve written about before and it’s truly a skill so I give a lot of my clients who are just starting out with OKRs a lot of grace here.

OKRs can be super powerful to narrow the playing field, create boundaries and provide focus.

However, you can also do the opposite if you’re not careful.

A high-level and broad OKR will cast a wide net.

For example, there are almost an infinite amount of ways to “increase revenue”.

Now, of course there's a ‘right sizing’ here.

You can’t go too low-level otherwise you’ll suffocate innovation and remove the freedom to explore alternative solutions but you also can’t be so vague that teams don’t know where to start.

Ok that’s it. I hope this is helpful.

If there’s something I missed or you’d like to add, I’d love to hear it!

And if you do need more help with OKRs, reach out! I’m happy to answer any questions you have and if you need something more hands on like coaching, check out the Product Mentorship, because that’s exactly what I designed it for!

Here’s a preview into what’s happening this month in the Product Mentorship — we’ve got a workshop on Product Metrics and North Star, along with the usual Office Hours.

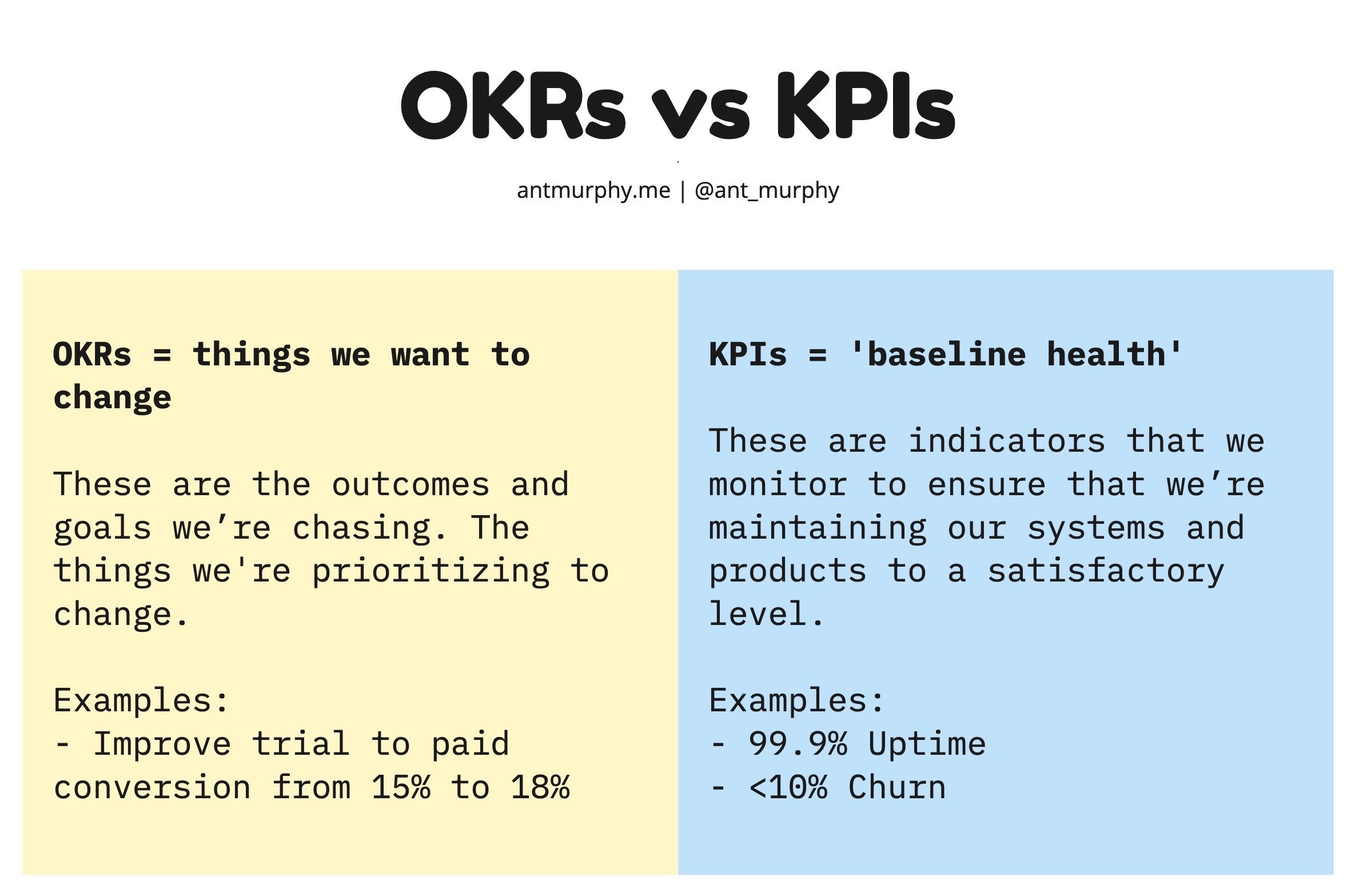

Your OKRs don’t live in a vacuum.

Yet this is exactly how I see many organizations treat their OKRs.

They jump on the bandwagon and create OKRs void of any context.

Here’s what I see all the time…